Making online discussions engaging

Authors

Piotr Teodorowski (PT), Saiqa Ahmed and Gosia Kasprzyk

Background

Ongoing digitalisation has encouraged researchers to conduct more interviews and focus groups online through video conferencing applications such as Zoom, Skype or Messenger (to name a few). Online data collection expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic as face-to-face meetings were difficult if not impossible to conduct, and online applications offered a safe alternative to traditional face-to-face meetings (Lobe et al., 2020). Building rapport with participants is crucial, and Deakin and Wakefield (2014) argue that it is possible to achieve rapport online, but it requires a different approach from researchers. This is especially relevant nowadays as working online has, for some, caused some zoom fatigue (Bailenson, 2021), so researchers need to take extra care to ensure online discussions engage participants. The cost and time benefits of conducting online sessions are well-established (Archibald et al., 2019, Deakin and Wakefield, 2014, Lo Iacono et al., 2016), but to what extent new tools can be utilised to make online discussions more interactive remains limited. This blog discusses our experience of conducting two online public involvement sessions. By reflecting on tools and approaches used during these sessions, we discuss the opportunities and challenges for researchers on stimulating online conversations.

Each group lasted two hours. This was longer than the recommended one-hour time to avoid fatigue (Gray et al., 2020), so we had 10 minutes comfort break. Five people took part in the South Asian group that was facilitated in English (out of five recruited) and four in Polish group that was facilitated in Polish (out of eight recruited). The focus groups took place on Zoom, a teleconferencing application that participants had to download and install in advance. As researchers, we had access to a paid plan which does not have time limitations (free version allows maximum of 40 minutes session). Zoom offers privacy, as only registered participants were admitted to the room (Zoom, 2021). During pilot sessions, limitations of using Zoom on a mobile phone were identified. We recommended that participants accessed the session through a computer or tablet to ensure that they could fully participate in every activity.

Sessions aims

• To raise awareness and engage with South Asian and Polish communities around public involvement in big data research.

• Develop capacity for future research projects by understanding how to successfully engage with South Asian and Polish communities.

• Explore the experience of using creative & interactive online discussion forums

• Test how the discussion would work in different language groups.

In this blog, we present our reflections on conducting interactive online group discussions.

Interactive tools

The session was interactive through the use of five creative tools to encourage the discussion. These were internal zoom tools (poll, whiteboard and screen share) and external (visual minutes and Padlet). Thus, participants expressed their opinions via different mechanisms, and their responses formed the basis of discussion. We present these tools in the order they appeared during the session. Firstly, we share our perspectives and then present participants views based on a short survey.

Sharing screen

Zoom allows sharing one’s screen with everyone simultaneously. We asked participants for feedback on the definition of big data research which could be used in future projects. One of the facilitators shared their screen with the Word document of our draft definition. Participants asked questions and made suggestions on how to improve this definition, and we updated it live so they could track any changes until everyone agreed with the final version. This went well, and it was easy for participants to follow all the alterations.

Padlet

Padlet is a tool that works like an online notice board where participants can post their notes as new sticky notes or answer to already existing ones. Initially, we published two questions on the board and we asked people to answer these questions by anonymously posting their responses below each question. These responses were then explored by the group. It took some time for participants to learn how to use the Padlet, but it worked smoothly once they became comfortable with this tool. For this reason, we kept adding questions to the board as the discussion progressed. Using Padlet also allowed shy participants or those who wanted to write anonymously to share their opinions on the board rather than speaking in the zoom call. After the session, one person emailed us pointing out that seeing discussion gave them “extra time to think about the questions”. We found the Padlet as one of the most successful and easy to use/learn tools throughout our sessions.

Polls

Zoom allowed us to set up polls in advance, and we used them throughout the session. One person who was accessing the videoconference through phone struggled with the first poll. The pools had to be predetermined prior to the session; this was more of a top-down approach to stimulate discussion rather than bottom-up (as the Padlet was).

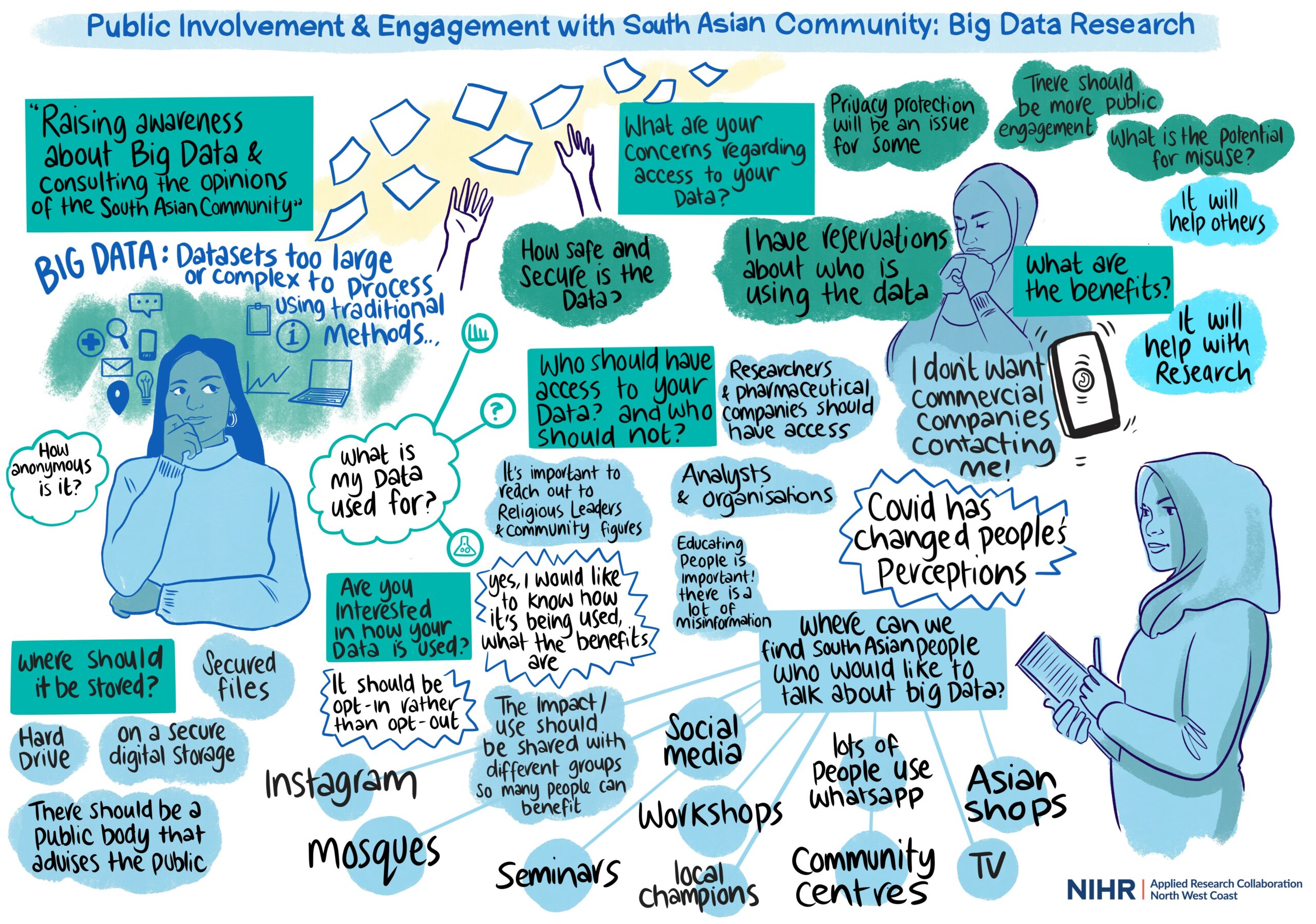

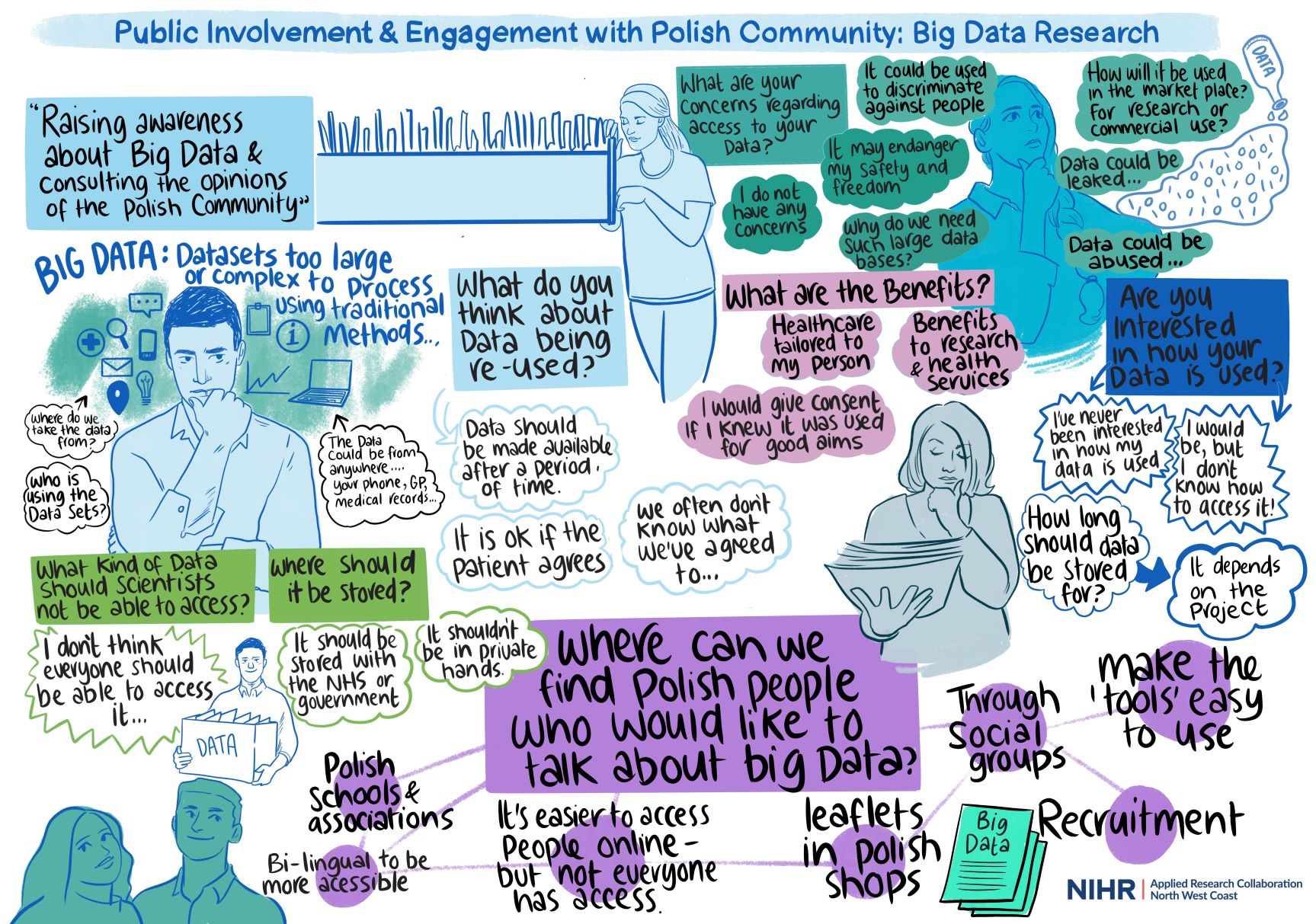

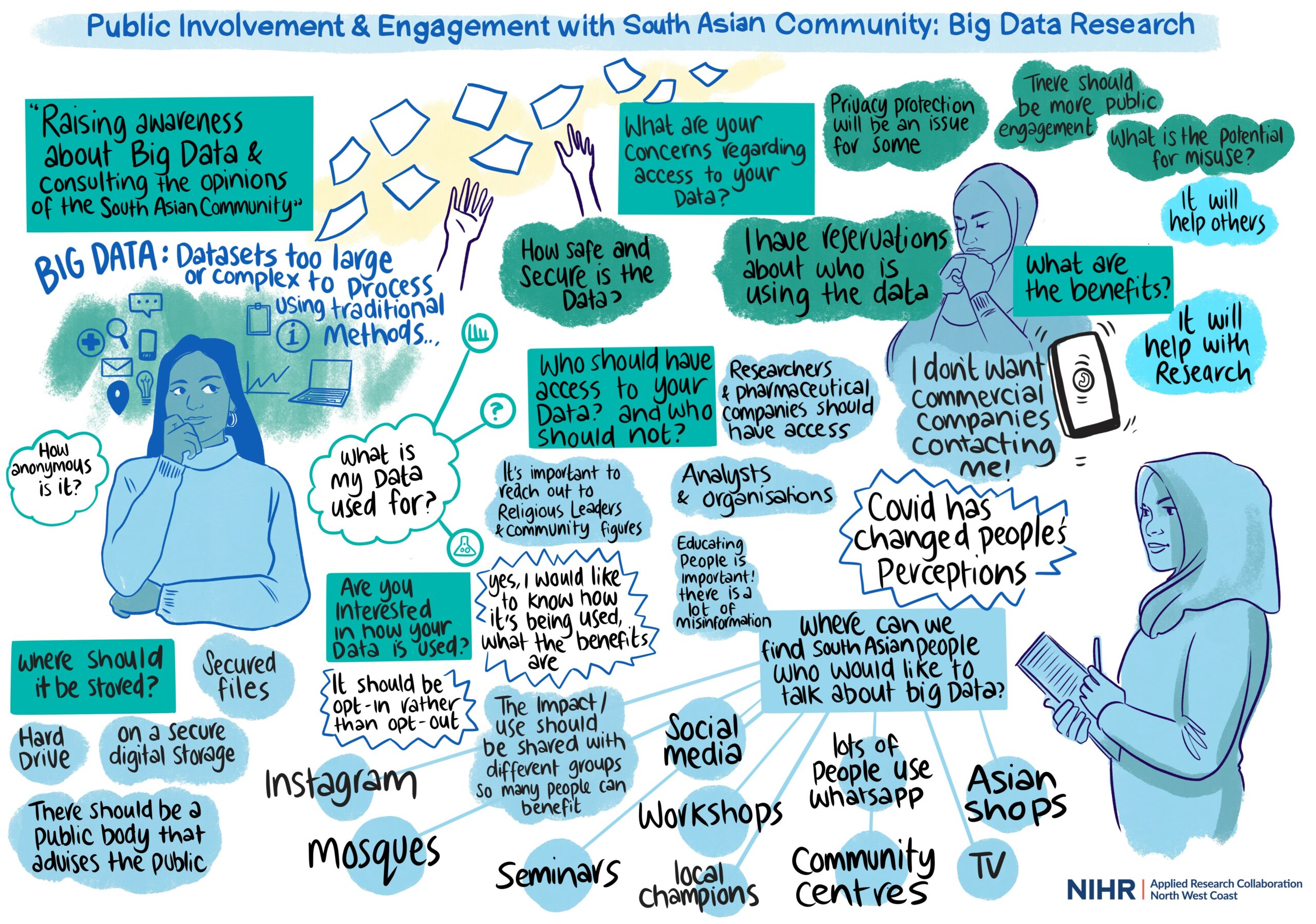

Visual minutes

credit: Ada Jusic Illustration

The illustrated record of discussion was created by the graphic designer who listened to each session (see figures 1 and 2 above showing the final result). During face-to-face meetings, participants can often see how the visual minutes are created by seeing them develop throughout the session. However, we decided to show the draft during the break and at the end of the session to allow participants to provide feedback. Participants’ commented on colour, graphics, and provided additional suggestions about content (especially in the Polish group). Participants were also offered an opportunity to provide further feedback on the visual minutes within 48 hours after the end of the session by email; one person used this opportunity.

The graphic designer ensured the gender balance in the representation of participants. South Asian participants also appreciated that women were presented in culturally appropriate clothes.

As the visual minutes were in English, there were concerns that participants in the Polish group might not understand them an thus be unable to discuss them. However, some participants pointed out that despite limited English skills, they were able to follow visual minutes because they were written in simple/plain English

Whiteboard

The Whiteboard feature allows all Zoom participants to annotate and draw in real-time on a virtual paper. We asked people to discuss how researchers can successfully reach and engage with participants’ communities. Everyone struggled to use the whiteboard. The major problem was that it took a lot of time for them to learn how to use the tool, and some stopped trying after a couple of unsuccessful attempts. As facilitators, we worked on computers and thus struggled to explain how to access drawing tools for people who were on tablets or phones. Those with poor internet connection pointed out that they could not draw a lot because drawings appeared with delay on their screen. The second facilitator tried to type some of the comments, but this option did not work as well as the Padlet.

Participants’ views

At the end of the sessions, we asked participants (n=8 as one person left earlier) to share their views on the interactive tools we used. T Responses to questions are detailed below. These support our reflections that the whiteboard was the least successful interactive tool as everyone found it challenging to use and for almost everyone it was the first time they encountered it.

Which interactive activities did you enjoy today?

Sharing screen (6)

Padlet (4)

Poll (5)

Visual minutes (4)

Whiteboard (2)

Which activity was easy to use?

Sharing screen (6)

Padlet (4)

Poll (8)

Visual minutes (3)

Whiteboard (2)

Which activity was challenging to use?

Sharing screen (0)

Padlet (2)

Poll (0)

Visual minutes (1)

Whiteboard (8)

Which activity was new to you today?

Sharing screen (0)

Padlet (4)

Poll (0)

Visual minutes (2)

Whiteboard (7)

Working in different languages

The South Asian group was facilitated in English while the Polish group was conducted in Polish (the participants’ mother tongue). As the graphic designer was not fluent in that language, we arranged an interpreter for Polish group. The graphic designer and the interpreter were part of the zoom call and connected on the phone where whisper interpreting was conducted (simultaneous interpreting what the interpreter was saying to the graphic designer and what was discussed in the zoom room). The interpreter was from an NHS-approved supplier, met with PT for a briefing around the session, and received the materials in advance. The graphic designer and the interpreter stayed after the session with facilitators for debriefing, mainly to record any cultural differences from the discussion. The interpreter described their experiences as:

“I found the session very well organised, pleasant to interpret, I enjoyed the interesting discussion. The interactive tools used during the session were useful, made my work easier. I have received plenty of guidance and support from the researchers regarding the discussion topics and technical solutions. The only minor challenge I encountered was some background office noise when I was on the phone with the graphic designer, I was just able to hear [the graphic designer], however being able to see [them] on camera helped a lot. ”

Some Polish participants pointed out that all information should have been translated into Polish or explained. In the final poll, we left words such as “Padlet” and “whiteboard” in English, which we had to explain as the vote was live.

What we feel could have gone better

Participants might not turn up on the day, even for face-to-face meetings. However, this was a challenge, particularly during the Polish group, where we overrecruited to compensate for possible absences. To ensure participant attend sessions, we sent them reminders on a day by email. A similar experience of participants not turning up for online appointments has been shared by others (Deakin and Wakefield, 2014). We would consider using phone text message reminders for future projects rather than emails as not everyone might check those regularly.

Technological difficulties will always be a part of conducting online discussions, but they do not necessarily have to negatively impact the on quality of conversation (Archibald et al., 2019). Lo Iacono et al. (2016) found that disconnection was not too problematic for rapport when conducting online interviews as it was easy to return smoothly to the conversation. However, we were concerned that some participants disconnected within focus groups might cause challenges for them to catch up with the discussion. Even when individual participants were disconnected, this was not too detrimental for the overall flow of conversation when we used creative tools as they easily could have tracked what had been going on since they left. Thus, in the future, we will ensure that some creative tools are always shared throughout the session.

Some further considerations for conducting online discussions

• Pilot a session with co-facilitators and if possible public advisors. We found that some of the online tools’ options (e.g. pools or annotation) were not activated and had to be changed manually in the zoom or Padlet settings.

• Share with participants details about which tools or apps (especially which particinats are unfamiliar with) will be used so they can explore them before the session. For example, some people tried to log in to the Zoom meeting a couple of days before the session to check if it worked.

• In different language groups, ensure that all words are translated or, if not possible, clearly explained to avoid confusion. Both English and translated version could be kept for clarity.

• Always involve two facilitators; for example, we found it helpful to have the second person ready to step in when one of our internet connections had problems.

• Ensure that all participants receive a reminder about the session that will be most helpful for them. Their preferences can be recorded as they sing up for the sessions.

About the research

This blog is based on PT’s doctoral research, which explores public involvement and engagement of seldom-heard communities in big data research. It shares an experience of conducting interactive online public involvement sessions which were utilised to underpin the PhD project research priorities and design. PT’s research involves public advisors who represent seldom-heard communities. They are involved in co-designing the study and have also acted as co-researchers (e.g. here SA was co-facilitator and recruited South Asian participants).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Naheed Tahir, Public Advisor with ARC NWC, who assisted in the session pilot.

Piotr Teodorwski is a PhD student supported by the National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration North West Coast (NIHR ARC NWC). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

ARCHIBALD, M. M., AMBAGTSHEER, R. C., CASEY, M. G. & LAWLESS, M. 2019. Using Zoom Videoconferencing for Qualitative Data Collection: Perceptions and Experiences of Researchers and Participants. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 160940691987459.

BAILENSON, J. N. 2021. Nonverbal overload: A theoretical argument for the causes of Zoom fatigue. Technology, Mind, and Behavior, 2.

DEAKIN, H. & WAKEFIELD, K. 2014. Skype interviewing: reflections of two PhD researchers. Qualitative Research, 14, 603-616.

GRAY, L., WONG, G., REMPEL, G. & COOK, K. 2020. Expanding Qualitative Research Interviewing Strategies: Zoom Video Communications. Qualitative Report, 25, Article 9.

LO IACONO, V., SYMONDS, P. & BROWN, D. H. K. 2016. Skype as a Tool for Qualitative Research Interviews. Sociological Research Online, 21, 103-117.

LOBE, B., MORGAN, D. & HOFFMAN, K. A. 2020. Qualitative Data Collection in an Era of Social Distancing. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 160940692093787.

ZOOM. 2021. Security Guide [Online]. Available: https://zoom.us/docs/doc/Zoom-Security-White-Paper.pdf [Accessed 20 August 2021].