COVID-19 and social care: the withdrawal of support services has negatively affected both people with dementia and their unpaid carers

People in the UK living with dementia and their unpaid carers (family members and friends) can access services such as day care centres, support groups, social activities in the community, or paid care after receiving a diagnosis. That is, if they are aware of these services, can afford them, and logistically access them. These services are offered by different providers, including third sector organisations and local councils.

Our qualitative interviews with 50 carers and people with dementia have shown us just the effect of the sudden withdrawal of social support services due to COVID-19 public health measures. During the nationwide lockdown, people with dementia were deteriorating faster due to the lack of social interaction and cognitive stimulation, as well as due to physical confinement. Although only a few weeks into the lockdown at the time of the interviews, carers were already expressing concern over how much more advanced their patient’s (often parent’s) dementia had progressed, rendering them potentially unable to access day care centres or support groups after the pandemic.

But we also wanted to quantify these negative experiences. That’s why, in a team of academics, clinicians, third sector organisations, and people affected by dementia, we developed a national survey to explore how access to social support services has been affected during the pandemic; and how usage or non-usage of these vital services is linked to anxiety, depression, and mental wellbeing. For this purpose, we developed an online and telephone survey for older adults, people with dementia, and current and former carers.

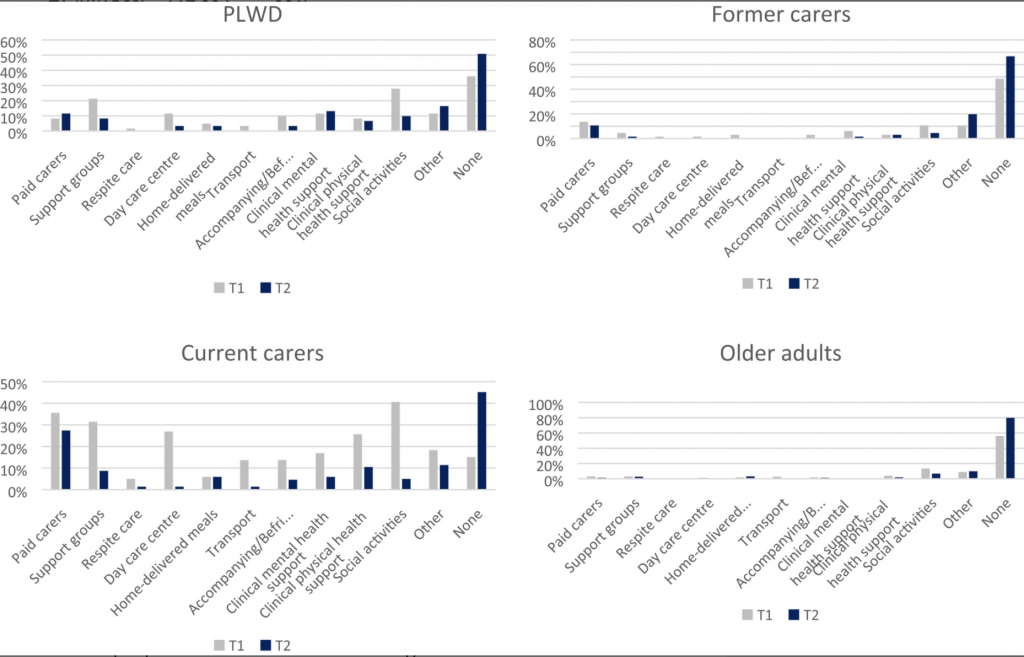

Between mid-April and mid-May 2020, over 660 people participated in our baseline survey. Of these, 569 participants had complete data. When looking at what people were accessing in a typical week before the pandemic compared to at that time point, service usage had decreased for all types of services – ranging from accessing support groups to day care centres. Paid home care seemed to be the least affected, which can be explained by some of our qualitative research into the decision-making processes of whether to continue or discontinue paid care. Many unpaid carers were afraid of letting in home carers for fear of virus transmission, particularly to their vulnerable and elderly relative with dementia. However, others made the decision to continue home care, as they could not cope otherwise.

Figure 1: Social support service usage before and since COVID‐19 lockdown by group.

Note: T1 = Before lockdown; T2 = Since lockdown. PLWD (People living with dementia).

What’s more, in our survey we showed that changes in social support service usage was associated with higher levels of anxiety in people with dementia and older adults, as well as with reduced mental wellbeing in unpaid carers and older adults. This has important implications for how some of the most vulnerable in our society need to be supported better in the wake of new restrictions. Specifically, there needs to be more and clearer guidance in place on how social support services, including day care centres and support groups, can provide continued support during this ongoing pandemic. Most support looks likely to be remote. But this raises questions as not everyone has internet access, and people in the advanced stages of dementia will need someone to support them in setting up Zoom meetings or Whatsapp groups, otherwise, they will have no access to these facilities. Some people might not be able to afford internet and a computer either, which might leave people from poorer backgrounds without access to services too.

What about face-to-face services? Some services can only be provided directly, such as paid home care, and even where services can be delivered remotely, many people are missing the direct contact with their peers. There need to be clear guidelines, both for community and for long-term care settings, on how people with dementia, carers, and older adults can interact with one another in a safe environment, taking into account social distancing and other measures where required, such as face coverings. If this is not done, and social support services are to continue being left to their own devices, we risk poorer mental health for some of the most vulnerable groups in our society. This is what we learned from the first lockdown. So surely we should be able to now adapt and improve this situation.

____________________

About the Author

Clarissa Giebel is a Research Fellow at the University of Liverpool and the NIHR ARC NWC. Her research focuses on enabling people living with dementia live independently and well at home for longer, and explores potential health inequalities faced. Her research looks at inequalities in care access on both a national and international scale.