Social Prescribing Week is the 4th-10th of March

Social prescribing - how are we doing when it comes to health inequalities?

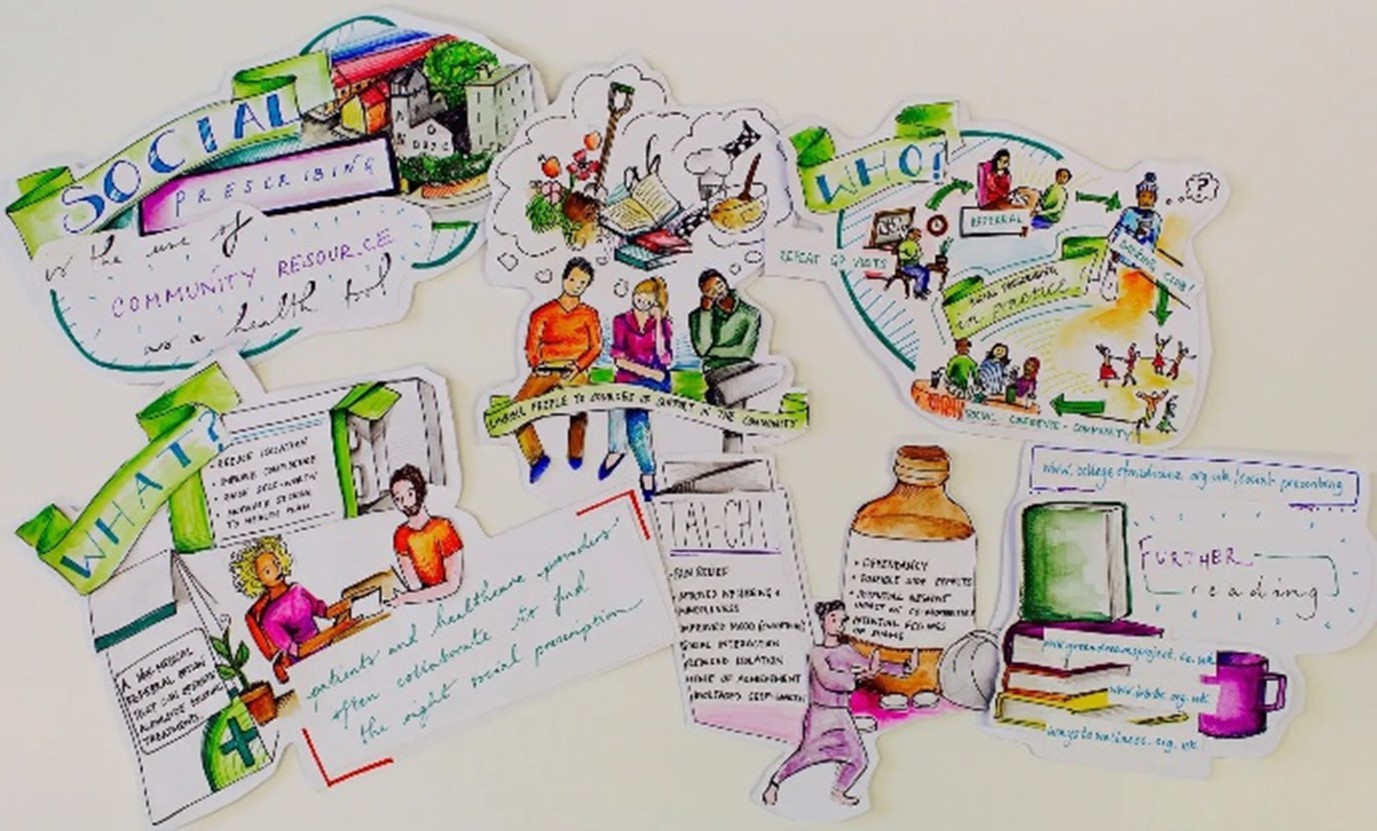

Social Prescribing is a widely growing intervention both within the UK and internationally yet you may ask what does this term actually mean and what does it do? At its simplest I would define it as connecting individuals to different types of local community support based on their individual needs. However, I do not want focus too much on how it works or its purpose here.

What I want to touch on is the grey cloud that surrounds social prescribing and that is the ‘lack of robust evidence’. Pick up any review on this topic and it will allude to the need for better evidence!1 One of the major criticisms has been the data gaps and insufficient information collected by services to properly evaluate the outcomes for service users.

In fact, this is something we found in our research project exploring the impacts of social prescribing on health inequalities. We wanted to take an equity lens to the data that was being collected but hit some hurdles.

Whilst we found basic demographic information (age, gender etc) was being collected, data on the wider determinants of health was not being collected. More importantly outcome measures that were being used to record impact were not always being completed. So ultimately, we could not explore if some groups had poor or better outcomes than others.

Looking through some of the reviews and papers on social prescribing it is difficult to find much that focuses specifically on demonstrating its impacts on health inequalities but you can find many a claim for how social prescribing can address health inequalities and statements such as:

“Social prescribing reduces health inequalities by addressing the wider determinants of health, such as debt, poor housing, isolation and physical inactivity.”3

“Social prescribing… is also effective at targeting the causes of health inequalities and is an important facet of community centred practice”.4

However, I would ask how can we evidence this if we are not collecting data that could help us demonstrate such impacts. More importantly how do we know that social prescribing is not actually fuelling inequalities. The need for this is quite simply emphasised in a recent paper exploring the ethical considerations of social prescribing.

“We should consider the impact of social prescribing on existing social inequalities. The “inverse care law” posits that those most in need of care are least likely to receive it, and vice versa. Almost by definition, the patients for whom social prescribing is imagined to be of greatest benefit are precisely those hard-to-reach groups who are less likely to engage (such as people who are socially isolated and struggling to establish supportive social relationships)”5

Therefore, quite legitimately we should be asking questions, who in fact is accessing social prescribing and who might not be? What might be contributing to this ? Are some groups having better experiences and outcomes than others if so why might that be? Collecting the right information will help us do this and based on our project findings we have created a short tip guide to help service commissioners and those involved in the delivery of social prescribing to think about the types of data they collect and how they can apply an equity focus to understanding the reach and impacts of their service. Our considerations include:

1. Who to involve?

2. Who is and who is not accessing your services?

3. How will you demonstrate the impact of our service?

4. What to consider when thinking about access?

5. What happens in your service?

6. How group characteristics affect outcomes?

7. Consider what might be influencing your findings

It is important to understand how services may impact different groups and influence outcomes we cannot just assume social prescribing is positively influencing health inequalities. Taking an equity lens to collect the right data and asking the right questions from the onset can help us do this!

Written by Koser Khan, Senior Research Associate at Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) North West Coast.

References:

1. Kerryn Husk, Julian Elston, Felix Gradinger, Lynne Callaghan, Sheena Asthana. Where is the evidence.British Journal of General Practice 2019; 69 (678): 6-7. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp19X70032

2. Julia V Pescheny, Gurch Randhawa, Yannis Pappas, The impact of social prescribing services on service users: a systematic review of the evidence, European Journal of Public Health, Volume 30, Issue 4, August 2020, Pages 664–673, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz078

3. https://www.onewestminster.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/social_prescribing_presentation_from_hw_sept_2019.pdf

4. Social prescribing: applying All Our Health – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

5. Brown, R., Mahtani, K., Turk, A., & Tierney, S. (2021). Social Prescribing in National Health Service Primary Care: What Are the Ethical Considerations? The Milbank Quarterly, 99(3), 610-628.