Podcast: Local green spaces and mental health

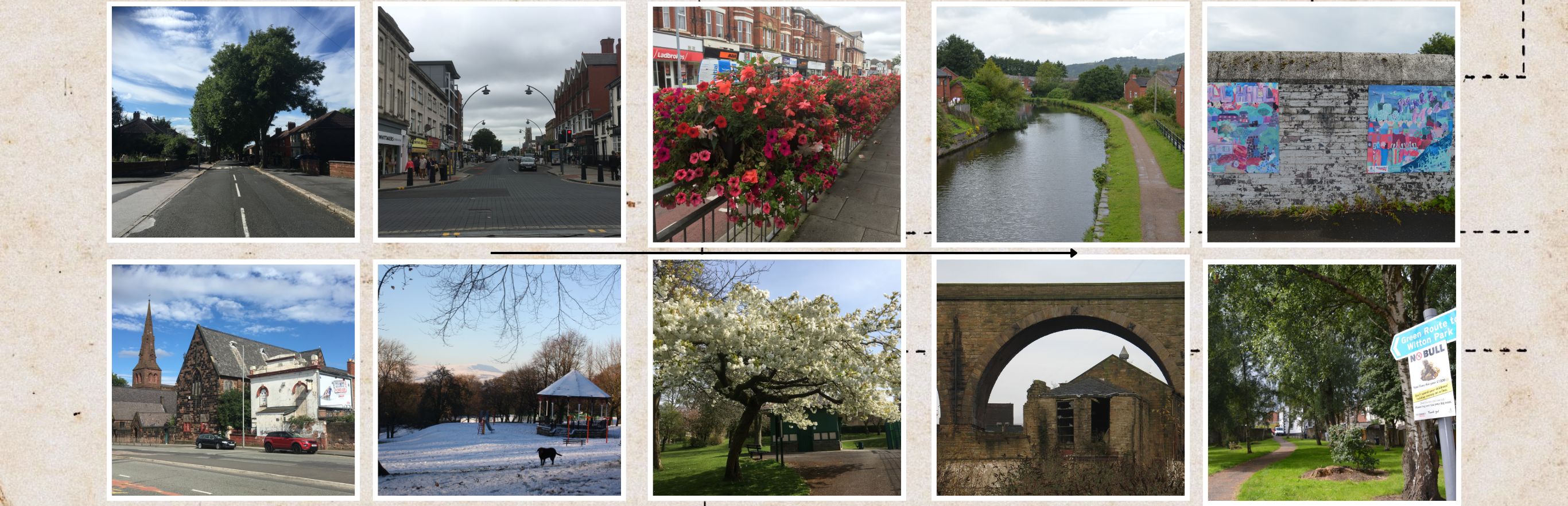

In this podcast, Helen Saul, Editor in Chief of NIHR Evidence, and study author Sarah Rodgers, Lead of ARC NWC’s CHI theme, discuss the impact of local green spaces on people’s mental health.

Researchers analysed data on more than 2 million people in Wales over 10 years to explore the impact of green spaces on mental health. They linked information about people’s mental health with information about the greenness of their home’s immediate surroundings and how close they lived to green or blue spaces (such as parks, lakes, and beaches). They found that people had a lower risk of anxiety and depression if:

• their home’s immediate surroundings (within 200-300 metres) were greener

• they could access green and blue spaces nearby.

The researchers say that local authorities could improve the mental health of their community by increasing the greenery in their towns and cities and improving access to green and blue spaces.

More information on mental health can be found on the NHS website.

The issue: how do green spaces impact mental health?

Green and blue spaces could improve mental health through the opportunities they provide to socialise and exercise; it could also be that these spaces improve air quality. But other factors, such as wealth, may explain this difference. Wealthier people tend to have better mental health and live in areas with more green space; it is unclear whether the improvement is linked with the wealth or the greenness.

This study aimed to tease out the impact of green and blue spaces alone, regardless of wealth or other factors. Researchers analysed how living in areas with more green space, or how close the nearest green and blue space was to someone’s house (access), affected people’s mental health. They also considered if the effect of green space on mental health differed between more and less wealthy areas.

What’s new?

The study was based on the GP records of 2.3 million people from Wales (aged 16 and older) from 2008 – 2019. The researchers searched anonymised patient records for a diagnosis of anxiety or depression, and for their home address(es). Each year, the researchers rated the greenness (trees, parks and gardens, for instance) of each person’s immediate home surroundings using satellite images. This was greenness that people could see from their front door; it required no effort to access. They also measured how close people’s houses were to green and blue spaces (within 1,600 metres), and the number of these spaces, using survey maps for each person, each year.

People who died or moved away from Wales were excluded from the study. If they moved within Wales, they were still included (along with the greenness of their new location). The researchers adjusted the results according to sex, age, deprivation and other factors.

Both measures of greenness (home surroundings, and local green and blue spaces) reduced the risk of anxiety and depression. The researchers found that:

• the highest level of greenness of home surroundings was associated with 20% less anxiety and depression than the middle level; the middle level with 20% less than the lowest level

• every 10% increase in access to green and blue spaces was linked with a 7% reduction in risk of anxiety and depression

people in poorer areas benefitted more (10% reduced risk of anxiety and depression) from access to green and blue spaces than those in richer areas (6% reduced risk).

• Every additional 360 metres from the nearest green or blue space was linked with a 5% higher risk of anxiety and depression. People with a previous diagnosis (anxiety and depression before 2008) benefitted more than others from green home surroundings, but not from greater access to green spaces.

Why is this important?

This is the largest, most comprehensive study to show that a green home environment, and access to green and blue spaces, protect against anxiety and depression. These findings support local authorities’ and policymakers’ efforts to add green spaces to towns and cities, and to increase access to them. This could improve the wellbeing of everyone, but especially those in deprived areas where the positive effects of green spaces were greatest.

A strength of the study was that it linked individual health records, to measurements taken over time of the greenness of home surroundings, and access to green and blue spaces. It therefore accounted for house moves or removal of a public green space, for example. The long follow up period (10 years) meant that changes in people’s mental health could be detected reliably.

People in poorer areas benefitted most from good access to green spaces, possibly because people in poorer areas are less able than others to make use of green and blue spaces further from home.

The study relied on primary care records to assess anxiety or depression; some people may have had either condition without seeking help from their GP. The quality of green spaces in terms of lighting, safety, or cleanliness, was not explored. It may be that living beside a poorly maintained park, for example, is not beneficial to mental health.

What’s next?

The researchers say increased greenery in towns and cities could improve mental health in the population, especially for people in more deprived areas and those with a history of anxiety and depression. Green and blue spaces have other benefits such as improving air quality, and providing habitats for wildlife.

The researchers suggest that policymakers and communities work together to improve access to these spaces and to ensure that the spaces meet people’s needs, and are well-maintained, for example. Green spaces that are accessible and safe, with security measures and ramps for wheelchair users, for example, are likely to bring most benefit.

The researchers are working with local communities on a project called GroundsWell, which is co-designing green and blue spaces with the aim of improving access. Another project, Healthy Urban Places, is bringing together researchers, communities, local governments, and other organisations to co-produce research on what makes a healthy place. For example, what features are most important for health, and how changes to local areas can improve health and reduce inequalities.